fragments.

This is the first piece in fragments. A series of lyric memoirs.

Nikki.

We tasted bright orange honeysuckles that grew from the neighbor’s concrete wall. That was about the time when you were born. An old wooden planter box in a neighbor’s yard grayed and splintered from the sun. Hot pavements in June, Southern California suburbs with concrete and birds of paradise, ice plant, and giant street lamps for miles.

Yellow fly traps hung from the ceiling, tiny prisoners wiggling their legs for hours. We wasted time by scratching our knees on the road, and rolling in the blunted grass, eating Mike’s baked barbeque chicken night after night.

Our house was crowded, chaotic, and the nights were dense and hot. Suddenly, I had a sister with dark hair and large eyes. You were a shrieking, colicky baby, oblivious to the fact that you were the climactic end note to our crowded house.

You were unimpressed with your place in the birth order, or was it just unaware? You certainly didn’t seem like a typical spoiled family baby. All you knew was your immediate world, us, and the house you lived in. But how else were you supposed to be? You shared a role in the family much like twins do: it was “Nikki and Tyler,” or “Tyler and Nikki” always. Every time.

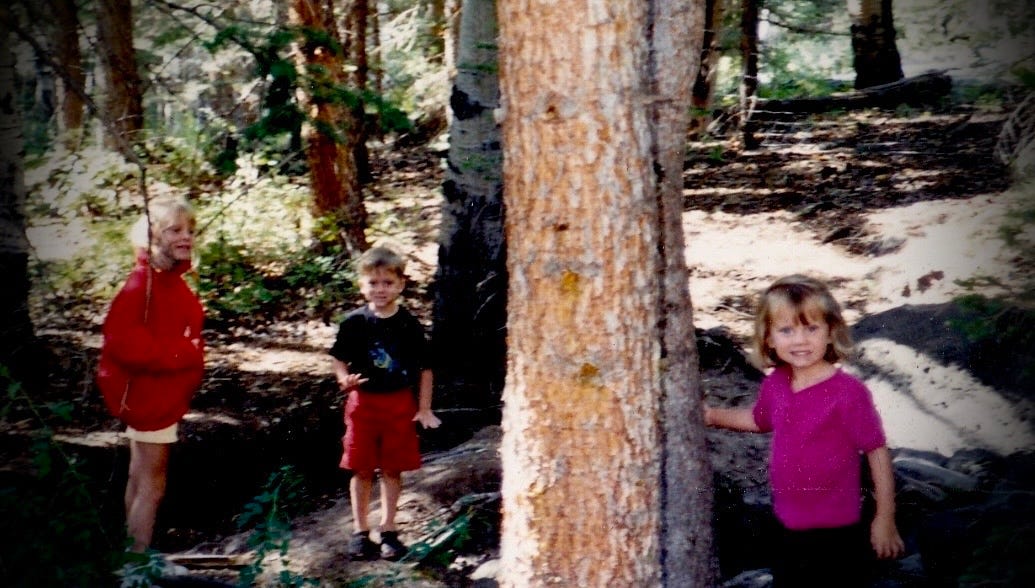

We lived in many houses, on Spanish roads in Spanish-named cities, Cartilla Ave, Alta Loma, and then on Orvieto Ct where the light poured into the entry-way glass and made rainbows on the floor. But like most places, we were there for only two years before it was time to leave, this time to a flat-roof house in Utah.

The night before, we called you in for dinner and we ate spaghetti and salad, and you and Tyler chased each other in circles in the entryway around us, shirts pulled over your heads, and we laughed as your bellies hung out. And then it was time for a bath, and we scrubbed the marinara sauce off of your skin. The next morning, we drove a packed truck far off into some wild far away desert.

We rolled up late at night to Grandma’s house in Kayenta, our tires crunched the driveway rocks, and the June bugs hissed from their nighttime places.

Do you remember that house? The coral pink walls in the backyard? We’d pretend we were gymnasts on a balance beam, scratching our thighs on the sharp stucco.

For me, the memory plays on repeat, and I suspect you have it there too: the air smells a bit like rust, and we are sitting on that wall staring into that vast ocean of blue sagebrush and red sand while Grandpa whisper-whistles in the background of our minds.

The sky pierced blue, and we’d go days without a single cloud in the sky. Grandpa cut giant slabs of sandstone and laid walkways looping around the house. As we watched him work, we crushed dirt clods in our bare hands. During the school year, you watched my school bus roll away down the melted tar roads.

Despite the heat outdoors, Grandma cranked the A/C on high, and that cold air bounced off the waxed brown tile floors. And you, tiny, and caramel colored, left old Halloween candy in my toybox. We drew tiny traffic lines in the tile grout with pencil and chalk, and when it was time to go outside, the sun baked the sand and burned the soles of our feet. Somehow, we enjoyed that kind of pain contrast: soft and hot.

One day, I packed a backpack with sandwiches, and we ran away into a dark gray storm on our bikes. We hid under the giant tunnel under the road, ate our lunch, and came back home so we wouldn’t miss Rugrats.

At night, you wore scratchy flannel pj’s, and I cut the tangled hair from the nape of your neck that stuck to the button. You swung wildly from the bunk bed frame at night, until I told you to go to sleep.

During the day, we lay belly down on the swings in the backyard. We swam for hours in the pool, came home and cuddled under sleeping bags on that scratchy brown couch. We shivered in our wet bathing suits, and our eyes stung-shut with chlorine until we fell asleep.

You ran around on the sharp gravel rocks with no shoes, barefoot and light, and you wore that Pocahontas costume every day while we slumped away to school, with stale cheetos and bruised apples in our lunch bags.

I built a tent with sticks and blankets in the backyard, and Scott came out with binoculars, and he mapped the shifting stars before we fell asleep. Do you remember the coyotes yelling at night?

But we were never well-rooted anywhere, and while we already knew, you were just finding out; homes were simply just houses, and it was again time to leave. We packed the van and trucks and left Grandma’s house for a green double-wide in a neighborhood that still had gravel roads and howling dogs.

That was the house where I found you under the bunk bed. Scott and I distracted you with stories, and I opened the window to let the howling inside, until you fell asleep.

We lived in a split-level blue house a block away for a short time, before the landlord kicked us out of there too, and we moved into a jerry-rigged brown house across from the elementary school. We took the dog to chase the sprinklers in the field, and watched the dusk settle as we heard her shouting out of the glowing yellow windows from home.

She blamed us. And I slept on the sofa upstairs in the corner by the window. Sometimes, I’d wake up and find you up there as well on the other couch, asleep, permed brown hair wild from a rough night.

The house creaked and the giant pine trees outside swayed, whispering secrets of our shame. We knew.

It was there that I realized I couldn’t hide it from you anymore, what it was I couldn’t really say; I didn’t even have the words. But I knew I couldn’t protect you from it. And yet, your awareness of that dark place helped us bond over some kind of unspoken hope.

We slept each night in that terrible, cement basement bedroom, and while you told happy stories of our futures, I started to believe in them too.